Peace Corps volunteers

A profile of who volunteers -- and the impact the service has on their education and professional development

What happens to former volunteers, who were predominantly in their 20s when they served overseas, as they continue their education and establish professional careers.See also: Peace Corps impact

Studies of Peace Corps volunteers

More than 190,000 volunteers have served in 139 countries since the inception of the Peace Corps in 1961.

Three major studies have been funded by the Peace Corps in its history – the first by the Harris polling organization in 1969; the second in 1977; and the latest in 1996 as part of a graduate thesis by Juanita Graul and the Peace Corps. At least 23 other narrower studies have been done of volunteers and they are summarized in the section, “Other studies of RPCVs”.

Three major studies have been funded by the Peace Corps in its history – the first by the Harris polling organization in 1969; the second in 1977; and the latest in 1996 as part of a graduate thesis by Juanita Graul and the Peace Corps. At least 23 other narrower studies have been done of volunteers and they are summarized in the section, “Other studies of RPCVs”.

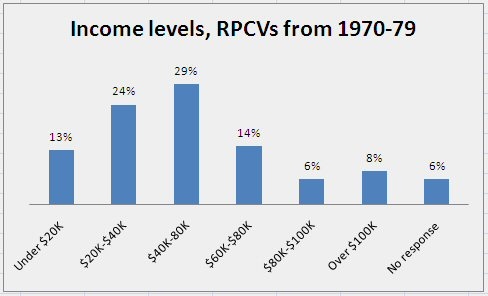

Invariably recent college graduates planning to join the Peace Corps hear, “Why are you waiting to start your career?” from friends, if not their parents. But the studies show that retruned Peace Corps volunteers (RPCVs) have high success measures, with older volunteers showing high and increasing income levels. In the 1996 study, 13% of the volunteers from the 1960s had income above $100,000 per year and a significant number were self-employed.

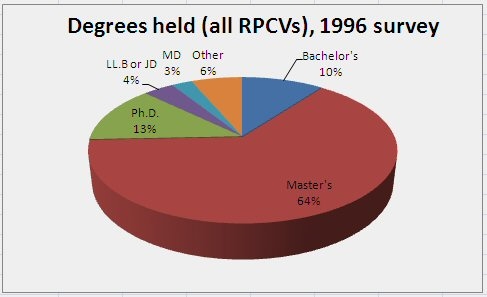

More than half of all volunteers had earned another degree since returning from foreign service, with another 10% saying that they were working on an advanced degree. By contrast, at the time the 1996 study was done, only 7.5% of all Americans held an advanced degree, according to U.S. Census Bureau data:

Though many volunteers worked in areas where regional or tribal languages were spoken, 63% said that they used a foreign language “occasionally” or “frequently” – a number that’s been very consistent across all three studies. In my case, having taught math & physics in French, 10 years later I would find myself briefing French computer engineers on personal computer technology — but in their native tongue. And more than 86% of the returned volunteers have traveled abroad again, with more than half (54%) visiting four or more countries and 25% having travelled to more than 10 countries. It can also change what you eat, adding things like chicken mwamba, sombe and samosas to your diet.

In their personal assessments, volunteers have consistently judged their service to have been “personally valuable” more than 90% of the time, though even in the first study done by the Louis Harris Organization only 46% judged their work to have been valuable to the host country – and 5% said that it did NOT contribute to the development in their host country.

Profile of volunteers

Despite efforts by the Peace Corps to attract people approaching retirement by advertising more to reach the target audience, the average volunteer age remains in the mid-20s. Volunteers today are even slightly younger than in 2004, when the average age was 28 and the agency had only 6% of its volunteers over age 50. Most have a college degree and by 1996 12% had an advanced degree.

However, new volunteers are older than they were in the early 1990s. During the 1990s, the freeing of Eastern European economies attracted a number of older volunteers with either work experience or an MBA. Volunteers worked on projects in Eastern Europe from the privatization of companies to the establishment of national parks and the marketing of the parks. The percentage of volunteers in the 18-29 age range has declined consistently, from 96% in the 1960’s to 93% in the 1970s and then to 79% by the early 1990s. The number of volunteers who were 30-39 rose from 3% in the 1960s to 11% by the 1990s. Why do people join the Peace Corps? From the 1996 study, RPCVs said:

75% wanted to experience a different culture

74% for travel and adventure

73% to help others

The Louis Harris study (1969)

Nine years into its history, the agency enlisted Louis Harris Associates to do a survey of volunteers from the 1962-66. There were 898 returned volunteers in the results. Two areas covered in later surveys — advanced education and professional development – were ignored in the initial study because too little time had since the volunteers returned home.

The New York Times headline: “Less Zeal Found for Peace Corps” masked the most-valuable aspects of this first major study of RPCVs. More than half of the volunteers reported difficulties adjusting to life when they returned to the U.S. More than half said that life at home seemed dull after their experience working overseas.

It also revealed that:

* 90% recommended it to other college graduates

* 92% said it was “very valuable” to them

* 40% said it was “very valuable” to the United States

* 46% said it was “very valuable” to the host country, with 5% saying their work did NOT contribute to the development of their host country.

Whatever the volunteers found, the same New York Times story notes that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee voted the same day to cut Peace Corps appropriations by 10%.

The Winslow study (1977)

Though it didn’t get the splash of a press conference that the Harris study received, in 1977 E.A. Winslow and the Office of Special Services surveyed 210 RPCVs who had completed their service between July, 1974 and June, 1975. The study, which reached 10% of those who served, was an attempt to see if the 1970s volunteers were significantly different from the 1960s group. Winslow’s conclusion: they weren’t.

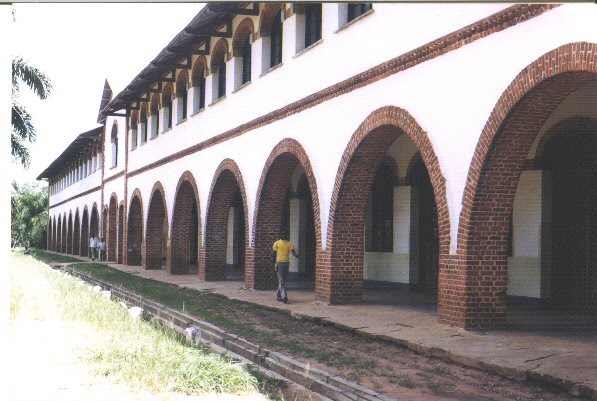

College Mala, a high school in Kasongo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the author taught while a Peace Corps volunteer. In 1973, when this photo was taken, the school graduated 65 students every year. Almost half of all Peace Corps volunteers have taught in high schools and universities.

The Graul study (1996)

Juanita Graul (RPCV, Jamaica, 1992-1994) prepared the latest study of former volunteers in cooperation with the Office of Planning, Policy and Analysis at the agency. “I had come out of Jamaica in 1994. I was an adult volunteer, celebrating my 50th birthday while I was in Jamaica. My particular concern was the crime rate and whether it was increasing or not,” she says. As a result, she worked with the Peace Corps to do the study as part of her 1998 thesis at Antioch University.

Graul finally got her wish to see the security issue examined when the General Accounting Office did a report in 2004, “Peace Corps: Observations on Volunteer Safety and Security”.

From the Peace Corps standpoint “a survey of returned volunteers had never been done adequately before,” says Pat Kasdan, a staff member in the Office of Policy, Planning and Analysis. The original Harris study from 1969 didn’t cover post-service education and professional development and the 1997 study covered only 201 volunteers. Interviewed in 2004, Kasdan said, “I remember the director (Mark Gearan) and the staff being totally shocked at the number of volunteers reporting sexual harassment.”

Kasdan, an early volunteer, adds, “It is important to compare the decades. Some of us from the first groups (1960s) were very critical. We’ve moved on to different stages of our lives. The older RPCVs get, the more they say they’ve gained.” “By contrast, someone who’s recently returned would dwell more on issues with their school, their supervisor, their friends in the country,” says Kasdan.

This latest study included 1,253 responses from volunteers who served between 1961 and 1993, so all respondents had been home for at least three years. Almost 137,000 volunteers had served during that time, but the Peace Corps had addresses for about 69% of former volunteers. The survey ran eight pages and was mailed to RPCVs.

NEW: RPCV comments on “Peace Corps Impact” from the 1996 study.

By decade the respondents were:

1961-1969: 42%

1970-79: 27%

1980-89: 12%

1990-93: 18%

Only 3% were older than 50 when they entered the Peace Corps and 90% were in the 18-29 age range. Those with a bachelor’s degree upon entry into the Peace Corps accounted for 78% of the respondents. Another 8% had “some college” and 12% had an advanced degree.

Juanita Graul’s conclusion was that “the Peace Corps experience has not changed appreciably over the decades”. But there are real surprises in the data, from the high incidence of sexual harassment to the fact that 5% of the respondents said that they would rejoin the Peace Corps after retiring.

For career measures, the 1996 study asked what impact volunteering had on future employment:

Been of great help

Been of some help

Not much difference

Slowed you down

Respondents over the decades were consistent, giving a 66% to 75% response to the “help” categories. Volunteers during the 1970s said that it slowed them down 6% of the time but for the other decades only 3% of those surveyed felt the same way.

As for where the RPCVs were employed, the 1996 study showed the following results. But there were enormous skews hidden with that data. For example, RPCVs from the 1960s accounted for 65% of the self-employed, though they were only 42% of the sample.

Also, men were over-represented in business (72%) and women in education (55%).

One of the surprises is that only 62% of those surveyed were married. In 24% of the cases, RPCVs were single and another 10% divorced or separated.

Comparative data

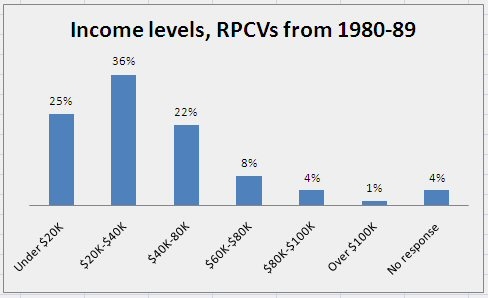

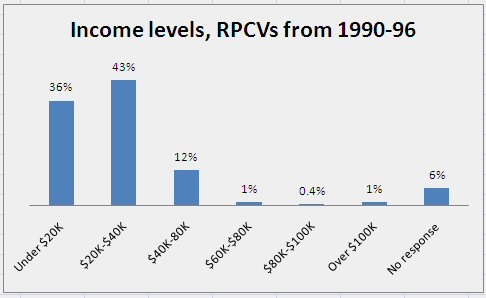

As might be expected, income levels grew with age and experience. Those from the 1960s were twice as likely to have an income above $60,000 per year than their colleagues from the 1970s – and 10 times as likely as an RPCV who left the service in the 1980s. Personal income for respondents from each decade breaks down this way:

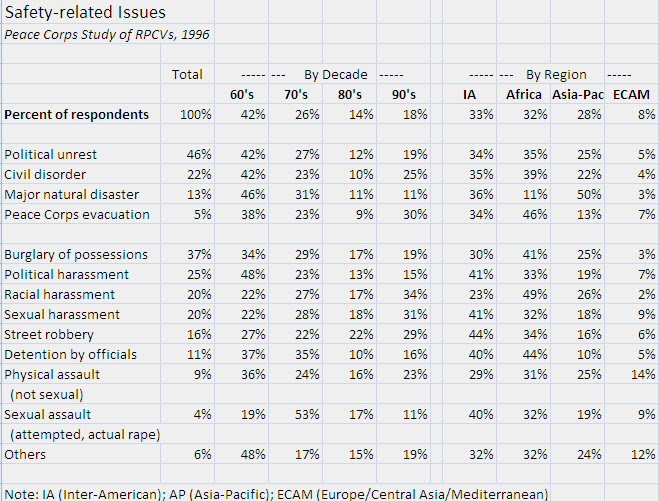

As for the safety-related issues that spurred Juanita Graul to propose the 1996 study, there were dramatic shifts away from political harassment to sexual harassment and street robbery over the decades. Political or natural disaster incidents were flat across the years – except for the 1990s, when Peace Corps evacuations rose suddenly. But there were large differences depending on where volunteers served, as the Asia-Pacific region had a low proportion of sexual harassment, street robberies and detentions by government officials.

Graul also noted that women suffered the most from sexual harassment and attempted or actual sexual assault, being the victims more than 92% of the time (95% for harassment). Men were more likely to experience political harassment (65% of the cases) or be detained by officials (69%).

Notable RPCVs

Former volunteers have included several U.S. senators and several governors but no presidents yet. However, Pres. Jimmy Carter’s mother, Lillian, was a volunteer in India. She served in India during 1974-1976, returning just as her son took office.

Author Paul Theroux wrote his first collection of short stories while in Malawi (1963-65). In the book “Dark Star Safari” he goes back visit both Malawi and Uganda (where he taught at the university after his Peace Corps service).

Chris Matthews, host of NBC’s “Hardball,” was a volunteer in Swaziland (1968-70) as was TV home repair guru Bob Vila (Panama, 1969-70).

There is one U.S. senator: Christopher Dodd, D-CT, (Dominican Republic, 1966-68). Paul Tsongas, D-MA, was the first former Peace Corps volunteer to serve in the Senate (starting in 1979). There have been two governors: Jim Doyle of Wisconsin and his wife, Jessica, were both in Tunisia, 1967-69. And Ohio’s Robert Taft, a Republican, who led that state as governor from 1999-2007, was in Tanzania, 1963-65. And lots of us have been successful in business. When you see how poorly government enterprises are run in some countries or get to witness a good kleptocracy at work, it can make you an ardent capitalist. Some well-known business people who are RPCVs include:

Frank Buzzetta, CEO of Hecht’s (India, 1968-1972)

Robert Haas, chairman of Levis Strauss (Ivory Coast, 1964-66)

Michael McCaskey, chairman of the Chicago Bears (Ethiopia, 1965-67)

Tim Scanlon, a well-known computer industry analyst who’s president of Benchmarks (Chile, 1961-63)

Kathy Tierney, CEO of Sur La Table (Fiji 1967-69)

Priscilla Wrubel, founder of The Nature Company (Liberia, 1961-63

For a continually updated list of well-known RPCVs, see these Peace Corps pages:

Peace Corps, “Notable Former Volunteers”

Arts & Literature

Business & industry

Communications

Nonprofit organizations

Government

Education

Foreign service

Books about the Peace Corps experience

One of the finest places to look for either fiction or non-fiction is the Peace Corps Writers website. It started as a 6-issue-per-year newsletter in 1989 and changed to the web-only format. Run by John Coyne and Marian Haley Beil they give out six awards each year at the National Peace Corps Association conference for best fiction book, best nonfiction book, best poetry book and best short piece — all by Peace Corps writers. Their current list has more than thousands of books by 950 RPCVs – and more written by Peace Corps staff members.

Peace Corps Writers

“About Us”

Links to a collection of more than 1,000 books by Peace Corps staff and RPCVs.

The Peace Corps itself put together a “Recommended Reading” list for Peace Corps week in 2008 that includes four works of non-fiction and four books written by RPCVs for children.

Peace Corps

“Recommended Reading”

One of the books that shows up on many RPCVs list is Mike Tidwell’s “The Ponds of Kalambayi”, Lyons and Burford, 1990. Tidwell was a fish culture extension agent in the Congo (then Zaire) from 1985-1987. His job was to increase the protein content of local diets in the Tshiluba-speaking region of the south central Congo. If his clients were successful they’d also generate cash from the tilapia ponds. He learns (slowly) the value of trust – and is surprised that success brings its own problems.

One of the books that shows up on many RPCVs list is Mike Tidwell’s “The Ponds of Kalambayi”, Lyons and Burford, 1990. Tidwell was a fish culture extension agent in the Congo (then Zaire) from 1985-1987. His job was to increase the protein content of local diets in the Tshiluba-speaking region of the south central Congo. If his clients were successful they’d also generate cash from the tilapia ponds. He learns (slowly) the value of trust – and is surprised that success brings its own problems.

Tidwell’s book is well-written, coming to a climax in one chapter. The chapter is good enough to stand alone, so Geraldine Kennedy picks it and a dozen other stories in “From the Center of the Earth: Stories out of the Peace Corps”, Clover Park Press, 1991. Kennedy’s collection is made up of all non-fiction tales from around the world. The book adds maps at the introduction to each, so that the reader has some idea where the locale is within a country. Like Tidwell, Kennedy is an RPCV (Liberia).

Karen Schwarz, author of “What You Can Do for Your Country: Inside the Peace Corps, a 30-year History,” is not a returned volunteer. In 1982, two years out of college she considered becoming a volunteer. But when she realized that the work might be arduous and living conditions tough, “I realized I would not last two weeks, let alone two years.” Still, she’s assembled one of the half-dozen histories of the Peace Corps, tracking policy changes through administrations and into the George Bush, Sr. years, when Eastern Europe began to experiment with free market economies. The perspective as a non-volunteer makes it clear that the agency is part of the government and as such is subject to the policy decisions of politicians in the administration.

A recent book, "Blaming Japhy Rider", by Philip Bralich details what happened in the 30 years after an accident in Togo that killed his wife and cut short his job teaching English.

RPCV organizations

National Peace Corps Association

Incorporated in 1983 as the national association to connect, inform and engage people impacted or inspired by Peace Corps. It is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization encompassing a network of over 30,000 individuals and more than 130 member groups.

RPCV Directory at Peace Corps Online

Chicago Area Peace Corps Assoc. (CAPCA)

Directory of Peace Corps links

Peace Corps Writers

Run by John Coyne and publisher Marian Haley Beil (both Ethiopia 1962–64), an RPCV once told me, “It seems as if John knows everything connected to the Peace Corps.”

Directory of regional RPCV organizations

Other studies of RPCVs

Listed by date:

“Age Differences in Volunteers’ Reaction to Overseas Service,” Allard and Wrigley, 1965

A “close of service” questionnaire from 1,530 RPCVs found that younger volunteers had more difficulties than older ones in adjusting to life overseas, though the 24-30 year olds had the lowest termination rate.

“Volunteers for Peace,” Stein, 1966

A survey of 62 young men who served in the first Peace Corps group in Colombia. The Peace Corps seemed to be a “psychosocial moratorium” for the volunteers.

Psychiatric Opinion

“Psychological Adjustment Patterns of PC Volunteers,” English and Colmen, 1966

Psychiatrists looked at volunteers evacuated in a crisis and compared them to RPCVs who finished their normal 24-month term, finding a far higher rate of depression. Some new strategies were suggested for dealing with re-entry problems.

“Survey of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers,” TransCentury Corp., 1969

This study, done in May 1969 with the Peace Corps, looked at volunteers who terminated service early, though it found no significant difference between that group and volunteers who finished a normal two-year term. There were 7,209 responses but only 541 from early terminees. More than half of all (57%) asked for more career support. They did not ask for higher pay.

“The Returned Volunteer: A Perspective,” Longsworth, 1971.

A study of 3,500 questionnaires, the study describes RPCVs as “uncommonly strong-willed, self-confident, practical minded intellectuals who place a low value on material goals and are contemptuous of bureaucracy.”

“Analysis of Former Peace Corps/VISTA Questionnaire,” Toote, 1972

Almost 3,700 RPCVs responded to this survey, most seeking added information on post-volunteer employment.

Journal of Youth and Adolescence

“Changes in Young Adults after Peace Corps Experiences: Political-Social View, Moral Reasons and Perceptions of Self and Parents,” Haan, 1974

A study of 34 women and 43 men found a shift to “political liberalization, greater open-mindedness and self-determination, greater detachment from their parents and increased incidence of principled moral reasoning.” Men and women had different types of personality changes.

“Growthful Re-Entry Theory: A Pilot Test of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers,” Adler, 1976

Uses a growthful re-entry model on 35 RPCVs.

“Impact of VISTA and Peace Corps Service on Former Volunteers and American Society: Phase I Report,” Smith for Contract Research Corp., 1977

The study was done on 929 people, including some who turned down a Peace Corps assignment. Former volunteers felt that they were more mature than others their own age and 70% felt that they were also more tolerant.

“Recommendations for Former Peace Corps and VISTA Volunteer Programming – Final Report,” Independent Foundation (1978)

The foundation, an organization of RPCVs, surveyed 3,066 former volunteers by phone and mail, advising increased career assistance and creation of a former volunteer directory.

“A Survey of Former Peace Corps and VISTA Volunteers: The Post Peace Corps Experience,” Contract Research Corp. (CRC), 1979

More than 5,000 RPCVs and VISTA volunteers were surveyed from the years 1968-1976. This is the first study to report that the majority of RPCVs return to school after service.

“Culture Shock Among Peace Corps Volunteers,” Leech, 1985

A survey of 47 RPCVs who had returned home within the past 5 years. Most of those responding said that they had difficulties adjusting (53%) and 45% indicated some level of depression.

“Returned Peace Corps Volunteers Can They Go Home Again?” Olsen, 1985

This study was of 70 RPCVs from groups in 1961 and 1982. Between one-quarter and one-third of the volunteers had difficulty re-entering, though the majority said they did not.

“Return to Society: Problematic Features of the Re-entry Process,” Jansson, 1986

RPCVs were one of four groups studied for re-entry problems. Jansson said the most-common problems were euphoria/denial, anger, sense of powerlessness, fear of rejection, immobilization and intimacy problems.

“The Peace Corps Experience: Its Lifetime Impact on U.S. Volunteers,” O’Donoghue and O’Donoghue, 1987

A survey of 437 volunteers that compared salary advances of RPCVs in New York City and Boston. RPCVs outperformed peers and even Fulbright Scholars with overseas experience.

“The Effect of Peace Corps Service on RPCVs,” Mankowski, 1988

Returned volunteers who completed their service in 1982 were questioned about the relationship between their volunteer service and career. More than half of the 117 respondents said that they were employed in a job related to their Peace Corps work.

“Final Report from RPCV Pretest Survey,” NSI Research Group, 1989

A random sample of 375 RPCVs looked at their post-service volunteer activities. Thos most-committed to volunteering were those who served in the 1960s, middle aged (35 to 55), and both self-employed and in upper income brackets.

“The Impact of a Transition Workshop on Re-entry Anxiety of Peace Corps Volunteers,” Hatzell, 1991

A study of six Peace Corps “close of service” groups found significantly more re-entry anxiety among women than men.

“An Application of Expectancy Violations Theory to Intercultural Re-entry Shock,” Waddell, 1992

A study of 56 returned volunteers found that differences between the RPCV and family were greater than they were with friends.

“Readaptation of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers,” Adam, 1993

A study of re-entry difficulties of 11 RPCVs.

International Journal of Aging and Human Development

“Peace Corps Service as a Turning Point,” Starr, 1994

A study based on interviews with 21 RPCVs who served in the Philippines during the mid-1960s – then followed up with interviews 20 years later. “The evidence on both the subjective and objective dimensions indicate strongly that their Peace Corps experience served as a real turning point for the great majority of these participants,” J.M. Starr concludes.

Journal of Travel Medicine

“Psychological and Readjustment Problems Associated with Emergency Evacuation of Peace Corps Volunteers,” (Hirshon, Eng, Brukon, Hartzell, 1997)

A study comparing volunteers evacuated during a crisis with those finishing their full two-year tour. They found very high rates of depression (60%) among those torn from job and friends, twice the rate of RPCVs who left at the end of their term.

Reverse Culture Shock: The Peace Corps Volunteers’ Experience

with Reentry, Heather Fristick, December, 2005.

A survey of 215 returned volunteers indciates that 66% had difficulties re-adjusting to life at home. A higher percentage of women (71%) than men (57%) reported problems in this study.

Peace Corps

Safety of the Volunteer 2009

Office of Safety and Security study looks at safety issues and trends during years 2006 to 2009, though we've only linked the latest report here. The 2009 volunteer was female 60% of the time; in their 20's 84% of the time; single 93% of the time and 84% had undergraduate degrees.

References

Christian Science Monitor,

“World to Peace Corps: skilled volunteers needed”, Benequista, April 25, 2008

New York Times,

“Less Zeal Found for Peace Corps”, Smith, April 3, 1970

U.S. General Accounting Office,

“Peace Corps: Observations on Volunteer Safety and Security”, Ford, June 22, 2004

“Peace Corps Impact”, volunteers’ comments from Peace Corps/Graul study, December, 1996

Last updated: 12/17/2020

A collection of material written by Andy Czernek, of Mukilteo, WA.

Other websites maintained the author include:

* Fry Family of Ashland County, Ohio, a family genealogy site

* Sinking of the SS Golden Gate, the story of the fire and sinking of the steamship off Manzanilla, Mexico in 1862

Because the website has pages on dozens of topics from aircraft to Zenith, we recommend using the site search box below:

About the author of these web pages

* Mooney Events, a calendar and other resources for owners of Mooney Aircraft